Tunngasugitsi, atilihai, tikilluaritsi!

In August, I joined the 2017 Students On Ice Arctic Expedition for another season, working with an amazing team of students and scientists from around the world. Of all the ways I practice as an Arctic doctor and anthropologist, Students On Ice is easily my favourite. SOI brings together youth from across the circumpolar north and around the world, introducing them to each other and their Arctic home, in the company a singularly brilliant team of outdoor educators, scientists, and diplomats. While exploring the circumpolar world, SOI bravely impels us to look inward and outward to heal the harms of colonialism, inspiring youth to create new stories together that reconnect with place and tradition and take lead in creating new cultures out of the old.

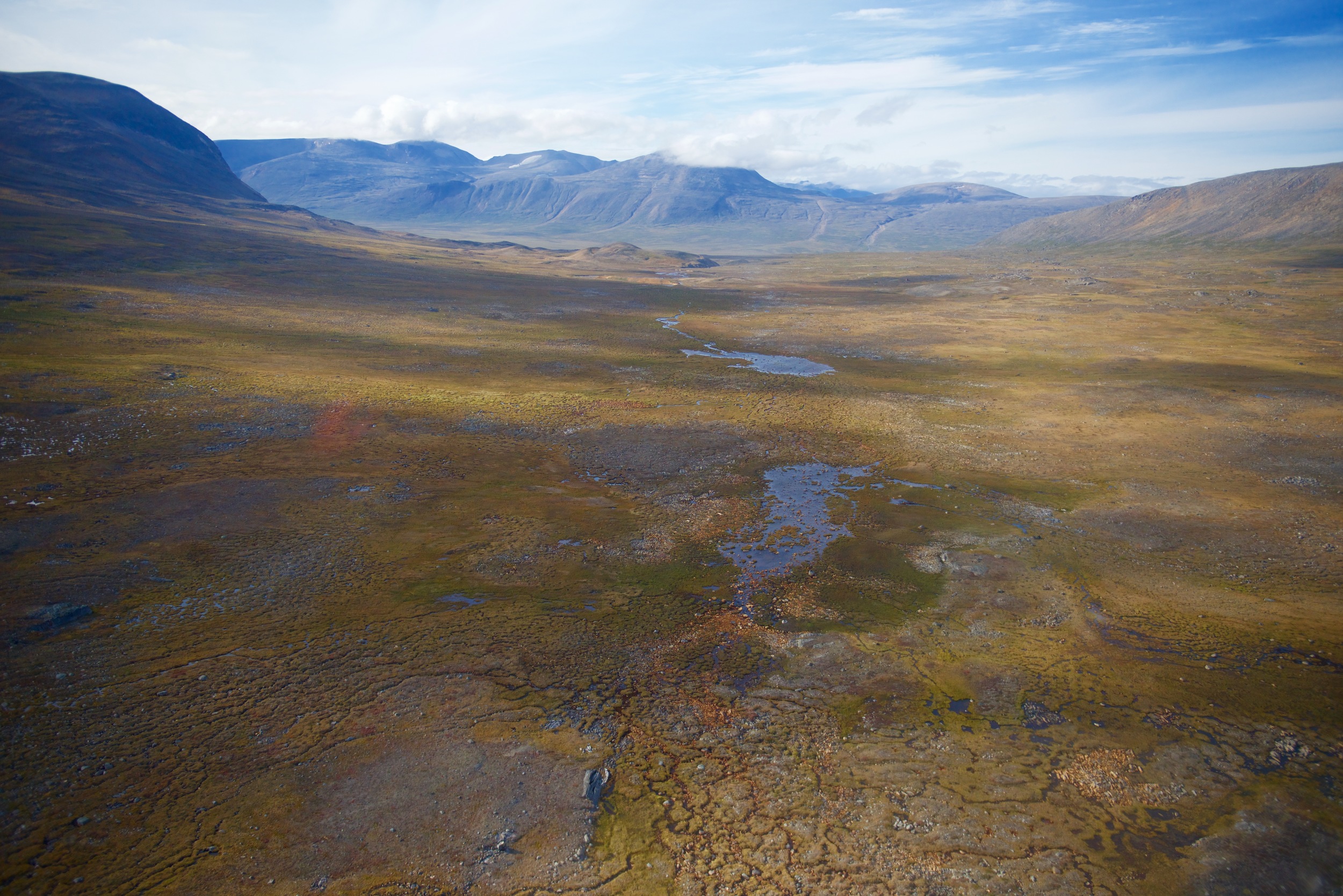

In the High Arctic, we visited Resolute to announce the creation of Qausuittuq National Park on Bathurst Island. We visited the incredible bird cliffs at Prince Leopold Island, and the Franklin graves at Beechey. We met the Canada C3 expedition as they circumnavigated Canada's three coastlines, visited the crew of the HMCS Montreal on patrol in Pond Inlet, and joined the announcement of Tallurutiup Imanga National Marine Protected Area, Canada's largest ever protected area (109,000km2). We explored Qaiqsut, an astonishing archeological site in Sirmalik National Park on Bylot Island with relatives of the Inuit who had lived there. We discovered a beautiful and previously unknown archaeological site at the mouth of North Arm Fjord in northern Baffin Island, now identified as "Site SOI 2017" by the Government of Nunavut. And we crossed the Davis Strait to Greenland, teaching and learning Arctic zoology, botany, oceanography, Inuit traditional knowledge, and the modern politics of Inuit Nunaat.

In Kalaallit Nunaat, we met youth in Uummannaq and heard stories from Ittoqqortoormiit (Scoresbysund), exploring the qajaq school, playing soccer, and making music with the community's amazing youth choir. We soaked in the long midnight sunset north of Disko Bay, sailing south to the Jakobshavn Icefjord in Illulisat, where we followed the footsteps of Knud Rasmussen and learned glaciology and climatology while icebergs calved before us. Exploring Itilleq, we learned how the community desalinates freshwater from seawater and enjoyed workshops along the wild shores of the Fjord. And in Kangerlussuatsiaq Fjord/Evighedsfjorden ("the fjord of eternity"), we fathomed the bird cliffs and watched icebergs calve from the Sermitsiaq Glacier as it drained the Maniitsoq ice cap, before jumping in for a swim.

It was an unforgettable journey of reconciliation that instilled in each of us a deeper knowledge of our Arctic home, amplifying our understanding of it's peoples, wildlife, and landscapes, and making them better known to ourselves and to the world. Travelling in the company of such an inspiring team of scientists and youth from across the circumpolar world and around the globe is a distinct and cherished part of my practice that I look forward to every year.

Qujannamiimmarialuk, Nakurmiimmarialuk, Qujanaq!

To learn more about the expedition, visit the Students On Ice website for more writing and short films, and explore my photos below.