This week I joined Joint Task Force Atlantic for Exercise Piulitsinik, a land, air, and sea search and rescue exercise in Torngat Mountains Mountains National Park, on the northern tip of Nunatsiavut.

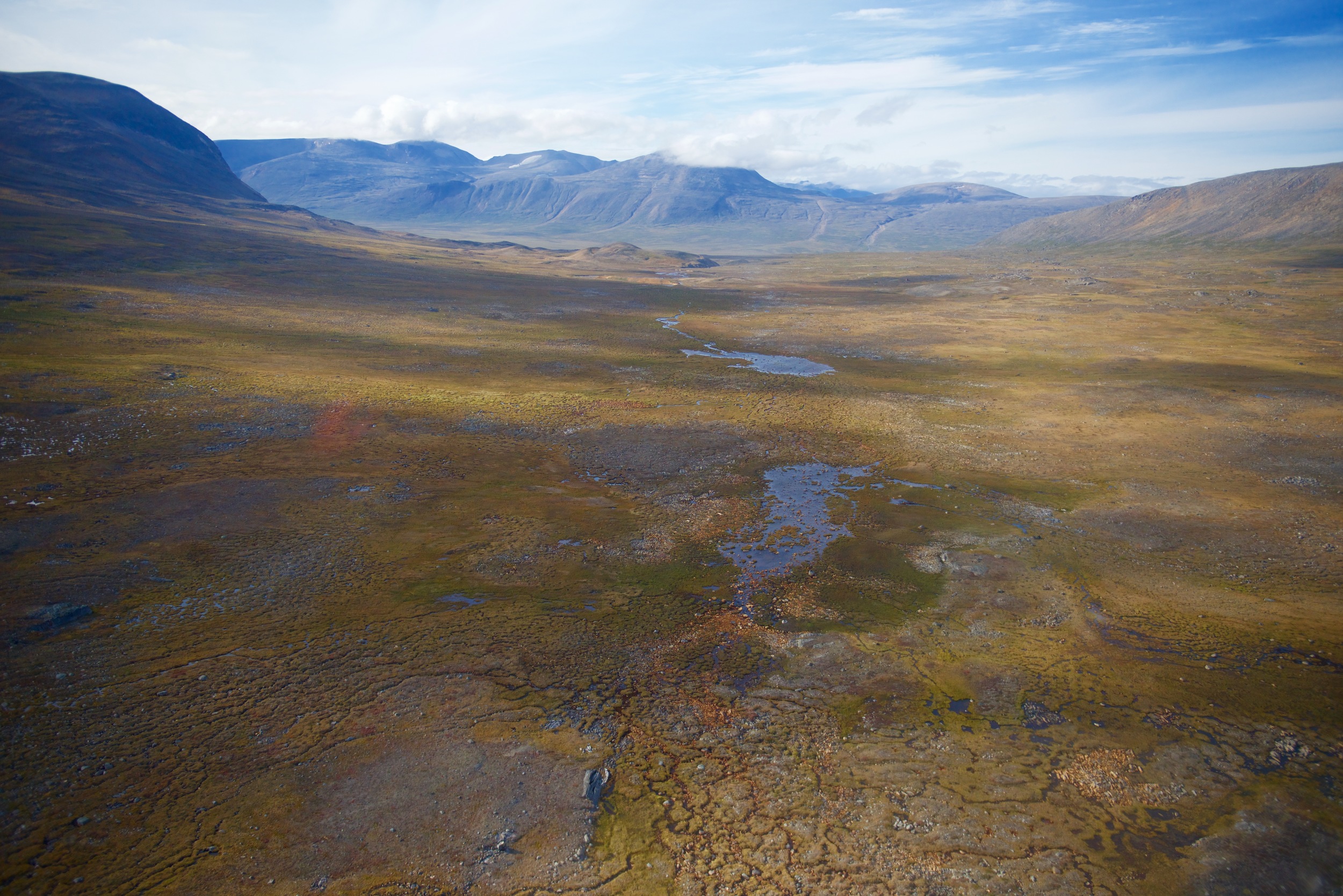

The Torngats are the most beautiful place I’ve seen - an arctic alpine tundra shaped by wild seas and deep fjords, full of whales, seals, caribou, barren ground black bears, and polar bears.

The exercise was the first of it’s kind in Labrador - a unique chance to test our emergency response abilities in this remote part of the Inuit homeland. It’s name, piulitsinik, comes from the Labrador dialect of Inuktitut, and means rescue.

During the exercise, we did a number of high fidelity simulations including a mass casualty scenario involving a zodiac flip and polar bear attack; water rescues; and a land and air search for a lost group of paddlers deep in the Torngat Mountains. As physician on the exercise, my job was to test our emergency response systems, offering high order medical insights during the search and rescue scenarios.

The exercise included members of the Army, Navy, and Air Force, including 444 Squadron’s Griffin search and rescue (SAR) helicopter out of Goose Bay, and 103 Squadron’s Cormorant SAR helicopter out of Gander, as well as staff from Parks Canada and Torngats Mountains Base Camp and Research Station. The exercise was filmed by members of the Okalakatiget Society for a documentary in English and Inuktitut to be broadcast on APTN in 2016.

Just getting these people in the same room - let alone together for a remote field exercise - was an incredible achievement, with an astonishing back story. In the summer of 2013, a polar bear attack in Labrador's Nachvak Fjord gave the Park an urgent sense of the need to optimize SAR capacity. By coincidence, I was on call the night of the attack as a medical student in Goose Bay's ER, and closely followed the survivor's story. The sheer number of bears we saw flying over the park by helicopter and exploring its islands and fjords by zodiac made me appreciate his unlikely survival even more.

Parks Canada carried this interest in rural and remote SAR with them to the high Arctic, where the discovery of a ship from the Franklin Expedition last fall brought their underwater archeologists into close contact with dive teams from the Royal Canadian Navy. This spring, Rear-Admiral John Newton and Parks Canada's Eastern Director Carol Sheedy met while visiting the ship and conceived the exercise, which came to life in just four months - a demonstration of their commitment to improving SAR capacity in the North.

The spirit of piulitsinik runs deep on the Labrador coast, where people live in intimate proximity to the land and sea. For most of us, the importance of optimizing search and rescue capacity on the coast hits very close to home. I was born in Makkovik, an Inuit community of 360 people on the north coast of Labrador. In February 2012, friends and family in my hometown desperately searched for Burton Winters, a young boy who'd become lost on the sea ice during a blizzard. The day I was invited to interview for a spot at med school was the same day my friends found his skidoo, stuck between blocks of jagged ice. For me, these experiences were inseparable; the relief of finding a path to medicine, and the heartbreak of my community mourning an unbearably preventable loss, became tributaries of the same river.

Search and rescue capacity is expensive. Compared to vaccines, or seatbelts, or oral rehydration salts, TB drugs, or lifesaving antibiotics, it's not the most cost-effective way to save lives. But it, too, matters. It's about a commitment to help, and not abandon people who are in trouble. It's about the kind of society and community we want to be - one that's ready to find and save, to look out for each other. It's about moral community.

Matt Damon's character articulates this idea in the film The Martian, suggesting "every human being has a basic instinct to help each other out. If a hiker gets lost in the mountains, people coordinate a search. If an earthquake levels a city, people all over the world send emergency supplies. This instinct is found in every culture, without exception." The film follows his character and team as they take this instinct, and "science the shit" out of it.

What are the boundaries of our moral community? Just as our readiness to pour resources into saving a lost hiker (or astronaut) speaks to the better angels of our nature, it also uncomfortably reveals the contradictions implicit in ignoring the suffering of far-away others. If we're ready to supply a Cormorant SAR helicopter to rescue sailors in the north Atlantic or paddlers in the Torngats, are we also ready to supply methotrexate for women with post-partum haemorrhage in Papua New Guinea, nutritional supplements for malnourished kids in the Sahel, mosquito nets and anti-malarials in Malawi, and clean drinking water in Attawapiskat?

In 2008, I met Dr. Paul Farmer, a physician and anthropologist who founded the group Partners in Health with fellow physician anthropologist Jim Kim (now president of the World Bank), and humanitarian Ophilia Dahl (niece of this other Dahl). When it came time to describe their mission, they put it this way: When our patients are ill and have no access to care, our team of health professionals, scholars, and activists will do whatever it takes to make them well—just as we would do if a member of our own families or we ourselves were ill.

This mission inspires my work as a medical doctor and anthropologist. It inspires the public ethics of search and rescue. It inspires public action in moments of global crisis. And it inspires the work of so many who accompany those who suffer close to home and in far away places while so much of the world looks elsewhere. It inspires us to think about what kind of society we want to be, what kind of people we want to be.